- Home

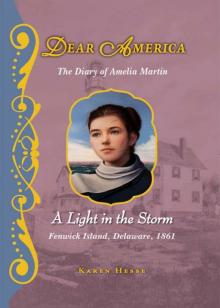

- Karen Hesse

A Light in the Storm Page 8

A Light in the Storm Read online

Page 8

Rain has fallen every day since Grandmother arrived. Today the decision was made to take Mother back to town with Grandmother. It is a decision we all knew would come, though Father put it off as long as possible, I think, for my sake.

Mother and Grandmother shall leave as soon as the weather clears. In the meantime, I have kept the fire stoked for Mother though it is August.

Abraham Lincoln has asked us to set aside the last Thursday in September as a day of prayer and fasting for all the people of the nation. It will be difficult to perform our duties and keep to the President’s proclamation, but we shall try.

Thursday, August 15, 1861

Fair. Wind S.W. Fresh.

Mother left with Grandmother this afternoon. Father and I took them across the Ditch. I looked over my shoulder at the familiar lines of the Lighthouse, the white conical tower topped with its black balcony. Mother looked back at it, too.

Father lifted and carried Mother easily to Commerce Street. We settled her comfortably in Grandmother’s bed.

After taking care of her at the Lighthouse through all these months of bad spells, I did not know how I could leave her today.

“Should I stay here with Mother?” I asked Father as we stood in Grandmother’s front room.

Father shrugged.

If I stayed, it would be just like before, when Father was gone at sea, and the three of us lived in the cottage together. I looked at Grandmother, more active than she has been in a long time. She has revived with Mother’s needing her. I realized it would be better for her to nurse Mother without me.

I chose to come back to the Light.

How odd it feels here on Fenwick without Mother.

Thursday, August 22, 1861

Clear. Wind N.E. Fresh.

Daniel is back! I am so filled with joy. He will be here for three weeks. Three weeks! I forced myself to do justice to my chores before Father and Keeper Hale told me I had done enough.

I rowed quickly to the mainland and stopped in at Grandmother’s, but Mother was sleeping. Then I raced to the Worthingtons’ in the moments I had before school. Daniel and I were awkward at first with each other.

But then we went out in the skiff after school, fishing. I dropped my line and sat quietly, waiting for Daniel to speak. Knowing if I could be still long enough he would eventually talk.

And he did start talking. He said it is so different here in Delaware. The way people talk about the War, the way they talk against President Lincoln. “The War is easier to understand when you discuss it with like-minded people.”

I asked him to explain it to me.

He told me the things I already knew. That the slave states wanted to expand slavery into the new territories, that their pride forced them to turn their backs on the Union when they could not have their way.

“Nothing can be accomplished by secession,” Daniel said. “The South has nothing to gain. This could have been worked out without leaving the Union. If they felt their rights were being invaded, the Constitution was there to aid them.”

I sat in the skiff, my line in the Ditch, the marsh and reed birds singing. And Daniel. It is a moment I shall always remember.

Daniel thought he might switch regiments. He said some of the officers are good men, but not all. “It helps to know the man who’s leading you. I’ve been lucky so far. There was a colonel I knew who didn’t care a fig about his men.”

Daniel gazed across the water. He sighed deeply, more deeply than the first time we really talked after his brother, William, died. “Our Government didn’t plan this War as well as it might have.” Daniel tilted his head, listening to the call of a reed bird. I could have watched him like that forever.

He said the rebel army is growing daily. But the three-monthers from the Federal army are being sent home. The capital is not adequately protected. Everywhere, there are too few Federal troops. They must bring the three-monthers back into position immediately. And the press must cease printing where the troops are, where they are heading, how many. “No wonder the rebels are taking the advantage.”

We sat in the boat a long time, quiet. “When do you think it will end, Daniel?”

“Prepare for a long war, Amelia. Bull Run was lost because everyone up North thought the War would be short. We thought that victory would be easy. We were wrong. We need a vast army, we need ample supplies. That’s the only way to win. The battle at Bull Run extended over seven miles. Seven miles of soldiers! Seven miles of death.”

We brought the fish we caught back to Daniel’s house. I shared an early meal with his family be-fore heading home for my watch. When I shut my eyes, even now, I can see Daniel in the boat with the reed birds behind him.

Sunday, August 25, 1861

Clear. Wind S.E. Fresh.

Keeper Hale led us in a celebratory service before chores.

Daniel rowed over early to help with the brass. He gets on well with Keeper Hale. I almost felt left out. But then Daniel had to rush back to attend regular church with his mother and sisters. I am glad for Keeper Hale in a hundred different ways, not least of which is the way he keeps the Sabbath.

Father brought Mother back to the station today for a visit. I was overjoyed to see her here, in her own home. We spent the day together. She looks better. I have watched her steady progress each day during my visits to Grandmother’s cottage.

How much better she is than when Father carried her out of here ten days ago.

She did not enjoy her time back on the island, though. Keeper Hale’s children buzzed curiously around her and Mother swatted them away like they were bothersome insects.

Father came upon us while I was brushing Mother’s hair in her old bedroom. She had made a new dress for me and I was wearing it. Father stood in the doorway a moment, watching us. His expression clearly showed what pleasure he took in seeing the two of us together like that. Then Mother caught sight of Father standing there and told him to leave at once. A wounded look crossed Father’s face for only a moment. Then he straightened, bowed, and was gone.

I took Mother back myself to Grandmother’s cottage and returned to Fenwick before sunset. I tried talking with Father about Mother when I returned. Father turned away.

Thursday, August 29, 1861

Fair. Wind S. Fresh.

School this morning. After checking on Mother this afternoon, I met Daniel and we hurried off to Uncle Edward. Uncle Edward visited with us for nearly an hour. He has a great deal of time on his hands these days. He says it would be so even if he was surrounded by Unionists. It seems the only businesses doing well in Delaware are those supplying the army — makers of shoes and coats and weapons.

He told us of a new business recently sprung up in the South — slave stealing. Uncle Edward says hundreds of men are descending on the eastern section of Virginia. There are plenty of slaves running loose there, slaves who have been deserted by their masters. These men take the abandoned slaves and convey them down to South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama, where they are condemned to slavery forever.

I was hardly able to take in that news when he told us that Jeff Davis has issued a proclamation ordering all Union sympathizers to depart within forty days. He means to seize their property, to fill his treasury.

What will happen to Keeper Hale’s sister and her family?

I tried to ask Father about this earlier tonight. He is still sleeping below, rather than in the house. In spite of his nearness, there is a great distance between us. It grows greater by the day. I asked him to come and sit with me awhile on my watch. He came but he hardly listened, not when I spoke of Union sympathizers in the South, not when I spoke of Daniel. When I was little, and he was a stranger, someone I saw only briefly with months of absence between, he used to pull my braid in teasing when I was hesitant to speak to him. He would look straight into my eyes. “Go on, Amelia,” he would say. As if everything on my mind was important to him.

There is no “Go on, Amelia,” now. Only distance.

&nbs

p; Thursday, September 5, 1861

P. Cloudy to Rain. Wind S.W. Moderate.

I am an official Assistant Lightkeeper with a salary, small but steady! I picked up the letter today at the post office. When I showed the letter to Father and Keeper Hale, they held a little ceremony for me. Then Father placed the letter in a box containing his most important papers.

I am considering giving up my duties at Bayville School in order to take on more here at the Light. It is hard for me to imagine not being in the classroom with my little scholars, but everything has changed since Mr. Warner’s departure. Perhaps I could help teach the Hale children here on the island, instead.

I stopped in on Mother and Grandmother this afternoon and the Worthingtons, too, to show Daniel the letter from the Lighthouse Board, but signs of a storm made me head back to the Light early, without a visit to Uncle Edward.

Daniel has one week more. The time passes too quickly.

Daniel walked me back to the skiff in the rain this afternoon. He had heard from someone in his regiment that the English were seeking, among their possessions, a place where cotton might be grown. Once they have a source of cotton other than our Southern states, the English will not need to wait for our blockade on the Southern cotton export to lift.

But what happens to the Negro who knows no other work than picking in the cotton fields if the cotton supply is no longer needed? Look what has come of the rebel’s temper.

In less than a month, all the people of Tennessee who adhere to the General Government shall lose their property. Those same Union sympathizers, if they choose to remain in the state of Tennessee, shall find themselves jailed.

Father, Keeper Hale, and I cleaned and inspected all the gutters and joints in anticipation of a strong blow. The cistern in the cellar is low. A good rainfall will do wonders for our supply of fresh water.

The storm is gaining strength, lashing around me now, as I stand watch. The wind is gusting, buffeting the tower. Spears of lightning are cast quickly toward the lantern room, then are swallowed by the bright flashing beacon of light. Thunder rolls in, regular as the wild waves, one crack rumbling into the next. The sky is fitful, with long legs of lightning kicking out every few seconds. The bell clangs for all it is worth. I cannot hear the bell in a storm without thinking of Mother.

Thursday, September 12, 1861

Fair. Wind N.W. Fresh.

Father left before dawn this morning, while Keeper Hale was on last watch. Father did not speak with me about the purpose for his leaving. He has not talked much with me since Mother came to visit last month. I have been thinking a lot about that visit. Mother was cruel to Father, crueler, in fact, than she was to the Hale children.

It troubles my spirit, these changes. The longer Mother is away from the Light, the happier and stronger she appears. But Father is not at peace. Even with Keeper Hale and his family around, Father rarely takes pleasure in the simple joys.

Daniel rowed out to tell me he has been given one more week before he has to leave. I am so grateful.

Monday, September 16, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind N.W. to N.E. Fresh.

Daniel and I pulled in a good number of crabs this morning before crossing the Ditch. The crabs fetched a fine price in town. I offered to give Daniel half but he refused. I gave the money to Grandmother, instead, to help pay Mother’s expenses.

This afternoon Keeper Hale handed me a copy of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He said I may keep it.

Thursday, September 19, 1861

Clear. Wind N.E. Fresh.

Father left the station early again. He gives no explanation. I wish he would have waited and crossed with me on my way to school. Perhaps in the skiff he would have talked. Daniel always talks in the skiff.

Saturday, September 21, 1861

Fair. Wind S.E. Moderate.

Uncle Edward says the crop this year was abundant after all, in spite of the late spring. So there will be enough for soldier and civilian to eat. France and England, suffering from rains and ruined crops, and Ireland, with its blight on the potatoes, are eager to purchase the sum of our surplus agriculture. Their purchases will place needed money in President Lincoln’s coffers.

Grandmother and Mother, with all that is going on around them, talked today only about the impertinence of shop girls. Mother’s color rose with anger as she described the Negro girl behind the counter at the millinery shop. Mother was angry because the girl’s dress was of a nicer cloth than she can afford.

A certain quality in Mother has been awakened by Grandmother. I am not certain I admire that quality, though I am grateful for what Grandmother has done.

Daniel’s regiment left today for Maryland. He did not come to see me this morning. There was no time.

I stand this watch, knowing Daniel is gone. That I might never see him again. That is a hard and constant ache.

But I stand my watch.

Sunday, September 22, 1861

Cloudy. Wind N.W. Moderate.

Keeper Hale led us in prayer, a more sober and plaintive service than he has held for us before. Two hundred thousand men, women, and children in the single state of Tennessee have received notice to leave the state of their birth because of their Union sympathies. Those who own stores have been assaulted as they resist the theft of their goods by the rebel pirates. I fear for Uncle Edward in a town where he is surrounded by secessionist sympathizers, at a time when emotions are running so wild.

Daniel has been gone only a day and already I miss him sorely. Who may I confide my troubles to now? Not to Uncle Edward. He has troubles enough of his own. Not to Father. He is silent as the floor of the sea. Not to Keeper or Mrs. Hale. I do not wish them to think me unstable and therefore ill suited for my job. That leaves only you, my diary. And Napoleon.

Earlier today, I gathered the five little Hale children around me and read to them from the Bible. They were good and quiet for at least three minutes. And then they were off chasing Napoleon, who is allowed to come in the house these days. Now that Mother is not here.

Thursday, September 26, 1861

Fair. Wind S.W. Moderate.

The glass was broken in Uncle Edward’s shop last night. And a fire set. I had a feeling something like this would happen.

When I saw what was done to my uncle’s shop, I feared for his life. I raced through the open door.

There was Uncle Edward, perched behind his counter. The lingering smell of smoke stung my eyes. “We’re fine, Wickie,” he said. “Don’t worry. Daisy and I extinguished the fire before it did any real damage.”

Uncle Edward sat straight, his eyes glittering. Daisy had a bandaged hand.

“They won’t drive me out,” Uncle Edward said.

I thought about the people in Tennessee. They were being driven out.

Our Governor refused to proclaim today as a day of fasting and prayer for deliverance from our troubles, as President Lincoln wished. The Mayor of Wilmington stepped forth and issued the proclamation instead.

The damage done to Uncle Edward’s store was meant to send a clear message about how the people of Bayville feel about President Lincoln and his proclamation.

Now I am on watch. I try not to notice the burn of hunger in my stomach as the hours of my fast go beyond fourteen

I dozed off!

The alarm bell woke me, letting me know that the clockwork had run down. Immediately I attended to my duties. My heart pounding, I checked everything, everything from the Light to the oil reserves, from the inky night sea to the bell-buoy boat.

All is well. Nothing amiss. I am lucky. I am so lucky that nothing went wrong in the moments I slept. That the Light stayed lit, that no ship went aground.

If anything had gone wrong, it would have been my fault. Lost property, lost life, it would have been my fault.

Thursday, October 10, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind N.E. Light.

I came softly upon Mother standing in Grandmother’s garden this afternoon.

I studied her before she was aware of my approach. She is so beautiful. Seeing her standing there, wrapped in her cloak, a bush of flaming red leaves behind her, it was easy to imagine how Father first fell in love with her. He used to tell me the story whenever I asked, about meeting Mother in Grandmother’s garden, and knowing the moment he saw her that she would be his wife….

The weather, up until yesterday, has been hot to the point of oppression, even with the ocean winds to cool us. The lantern room has been insufferable. But today it is cold, almost to freezing. And Daniel sleeps outside.

Thursday, October 17, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind S.E. Moderate.

Uncle Edward has let me work in his store in exchange for a flannel undershirt for Daniel. It is easier to find an extra hour or two for Uncle Edward now that Mother is with Grandmother. Together the two are able to handle the sewing, the ironing and baking, all the light chores I had been doing for Grandmother myself. They only need me now for heavy chores, lifting and carrying.

I have tried to send a package or letter to Daniel every week. He writes back nearly as often.

I think of Daniel among the long lines of fires flickering and glowing in the night—all the tired soldiers, eating their suppers, settling into sleep while only the sentinels keep watch.

I am one of the sentinels.

Thursday, October 24, 1861

Clear. Wind N.W. Fresh.

Father woke me at dawn, at the conclusion of his watch. As I climbed the spiral stairs to the Light to begin morning chores, Father took the scow across the Ditch.

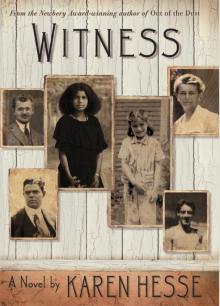

Witness

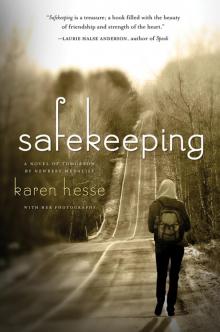

Witness Safekeeping

Safekeeping Sable

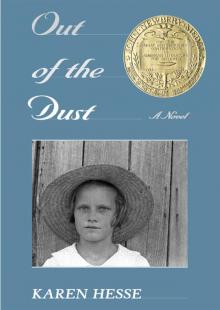

Sable Out of the Dust

Out of the Dust Letters From Rifka

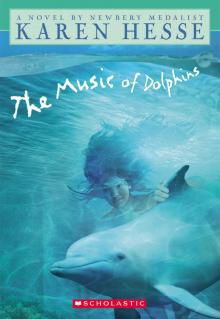

Letters From Rifka The Music of Dolphins

The Music of Dolphins Wish on a Unicorn

Wish on a Unicorn A Light in the Storm

A Light in the Storm