- Home

- Karen Hesse

Letters From Rifka

Letters From Rifka Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Historical Note

Copyright Page

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following people, whose counsel and expertise contributed to the body and soul of this work: Applied Graphics; Lucille Avrutin; Betsey Bonin and the Book Cellar; Eileen Christelow; Esther Evenson; Beverly Fischel; Ethel Gelfand; Randy, Kate, and Rachel Hesse; Sandra King and the Brooks Memorial Library; Randy, Ronny, and Marni Letzler; Fran Levin; Robert MacLean; Bernice Millman; Liza Ketchum Murrow; Cynthia Nau and the Moore Free Library; Howard Sacks; Arlyn Sharpe; Society of Children’s Book Writers/ Newfane chapter—in particular, Winifred Bruce Luhrmann, Cynthia Stowe, Michael Waite, and Nancy Hope Wilson; Starr Library at Middlebury College; Vermont Southeast Regional Library: Amy Howlett, Gwendolyn Jennings, Joan Knight, Deborah Tewksbury, and Sophia Wessel; and Kevin Weiler.

With special thanks to Brenda Bowen and Barbara Kouts.

In memory of

Zeyde and Bubbe,

my beloved grandparents

… and from

The gloomy land of lonely exile

To a new country bade me come … .

—Pushkin

September 2, 1919

Russia

My Dear Cousin Tovah,

We made it! If it had not been for your father, though, I think my family would all be dead now: Mama, Papa, Nathan, Saul, and me. At the very best we would be in that filthy prison in Berdichev, not rolling west through Ukraine on a freight train bound for Poland.

I am sure you and Cousin Hannah were glad to see Uncle Avrum come home today. How worried his daughters must have been after the locked doors and whisperings of last night.

Soon Bubbe Ruth, my dear little grandmother, will hear of our escape. I hope she gives a big pot of Frusileh’s cream to Uncle Avrum. How better could she thank him?

When the sun rose above the trees at the train station in Berdichev this morning, I stood alone outside a boxcar, my heart knocking against my ribs.

I stood there, trying to look older than my twelve years. Wrapped in the new shawl Cousin Hannah gave to me, still I trembled.

“Wear this in health,” Hannah had whispered in my ear as she draped the shawl over my shoulders early this morning, before we slipped from your house into the dark.

“Come,” Papa said, leading us through the woods to the train station.

I looked back to the flickering lights of your house, Tovah.

“Quickly, Rifka,” Papa whispered. “The boys, and Mama, and I must hide before light.”

“You can distract the guards, can’t you, little sister?” Nathan said, putting an arm around me. In the darkness, I could not see his eyes, but I felt them studying me.

“Yes,” I answered, not wanting to disappoint him.

At the train station, Papa and Mama hid behind bales of hay in boxcars to my right. My two giant brothers, Nathan and Saul, crouched in separate cars to my left. Papa said that we should hide in different cars. If the guards discovered only one of us, perhaps the others might still escape.

Behind me, in the dusty corner of a boxcar, sat my own rucksack. It waited for me, holding what little I own in this world. I had packed Mama’s candlesticks, wrapped in my two heavy dresses, at the bottom of the sack.

Your gift to me, the book of Pushkin, I did not pack. I kept it out, holding it in my hands.

I would have liked to fly away, to race back up the road, stopping at every door to say good-bye, to say that we were going to America.

But I could not. Papa said we must tell no one we were leaving, not even Bubbe Ruth. Only you and Hannah and Uncle Avrum knew. I’m so glad at least you knew, Tovah.

As Papa expected, not long after he and Mama and the boys had hidden themselves, two guards emerged from a wooden shelter. They thundered down the platform in their heavy boots, climbing in and out of the cars, making their search.

They did not notice me at first. Saul says I am too little for anyone to notice, but you know Saul. He never has a nice word to say to me. And I am small for a girl of twelve. Still, my size did not keep the guards from noticing me. I think the guards missed seeing me at first because they were so busy in their search of the train. They were searching for Nathan.

You know as well as I, Tovah, that when a Jewish boy deserts the Russian Army, the army tries hard to find him. They bring him back and kill him in front of his regiment as a warning to the others. Those who have helped him, they also die.

Late last night, when Nathan slipped away from his regiment and appeared at our door, joy filled my heart at seeing my favorite brother again. Yet a troubled look worried Nathan’s face. He hugged me only for a moment. His dimpled smile vanished as quickly as it came.

“I’ve come,” he said, “to warn Saul. The soldiers will soon follow. They will take him into the army.”

I am ashamed, Tovah, to admit that at first hearing Nathan’s news made me glad. I wanted Saul gone. He drives me crazy. From his big ears to his big feet, I cannot stand the sight of him. Good riddance, I thought.

How foolish I was not to understand what Nathan’s news really meant to our family.

“You should not have come,” Mama said to Nathan. “They will shoot you when you return.”

Papa said, “Nathan isn’t going to return. Hurry! We must pack!”

We all stared at him.

“Quickly,” Papa said, clapping his hands. “Rifka, run and fill your rucksack with all of your belongings.” I do not know what Papa thought I owned.

Mama said, “Rifka, do you have room in your bag for my candlesticks?”

“The candlesticks, Mama?” I asked.

“We either take them, Rifka, or leave them to the greedy peasants. Soon enough they will swoop down like vultures to pick our house bare,” Mama said.

Papa said, “Your brothers in America have sent for us, Rifka. It is time to leave Russia and we are not coming back. Ever.”

“Don’t we need papers?” I asked.

Papa looked from Nathan to Saul. “There is no time for papers,” he said.

Then I began to understand.

We huddled in your cellar through the black night, planning our escape. Uncle Avrum only shut you out to protect you, Tovah.

Hearing the guards speak this morning, I understood his precaution. It was dangerous enough for you to know we were leaving. We could not risk telling you the details of our escape in case the soldiers came to question you.

The guards were talking about Nathan. They were saying what they would do to him once they found him, and what they would do to anyone who had helped him.

Nathan hid under a stack of burlap bags, one boxcar away from me. I knew, no matter how frightened I was, I must not let them find Nathan.

The guards said terrible things about our family. They did not know me, or Mama or Papa. They did not even know Nathan, not really. They could never have said those things about my brother Nathan if they knew him. Saul, maybe, clumsy-footed Saul. They could have said hateful things about Saul, but never Nathan. The guards spoke ill of us, not because of anything we had done, not because of anything we had said. Just because we were Jews. Why is it, Tovah, that in Russia, no matter what the trouble, the blame always falls upon the Jews?

The guards’ bayonets plunged into bales and bags and crates in each boxcar. That is how they searched, with the brutal blades of their bayonets. The sound of steel in wood echoed through the morning.

I stood trembling in the dawn, Tovah, gripping your book in my hands to steady myself. I feared the guards would guess from one look at me what I was hiding.

Fo

r just a moment, I glanced toward the cars where Mama and Papa hid, to gather courage from them. My movement must have caught the guards’ attention.

“You!” I heard a voice shout. “You there!”

The guards hastened down the track toward me. One had a rough, unshaven face and a broad mouth. He stared at me for a moment or two as if he recognized me. Then he seemed to change his mind. He reached out to touch my hair.

This is what Papa hoped for, I think. People have often stopped in wonder at my blond curls.

You say a girl must not depend on her looks, Tovah. It is better to be clever. But as the guards inspected me, from the worn toes of my boots to my hair spilling out from under my kerchief, I hoped my looks would be enough.

I hated the guard touching my hair. I clutched your book of poetry tighter to keep my hands from striking him away. I knew I must not anger him. If I angered him, I not only put my life in danger, I endangered Mama and Papa and Nathan and Saul, too.

The guard with the unshaven face held my curls in his hand. He looked up and down the length of me as if he were hungry and I were a piece of Mama’s pastry. I held still. Inside I twisted like a wrung rag, but on the outside I held still.

Papa is so brave, the guards would not frighten him. I remember the time soldiers came to our house and saw on Papa’s feet a new pair of boots. Uncle Shlomo had made them for Papa from leftover pieces of leather. The soldiers said, “Take the boots off. Give them here.” Papa refused. The soldiers whipped Papa, but still Papa refused to hand over his boots. They would have killed Papa for those boots, but their battalion marched into sight. The soldiers hit Papa once more, hard, so that he spit blood, but they left our house empty-handed.

This was the courage of my papa, but how could he ever think I had such courage?

Courage or not, of all my family, only I could stand before the Russian soldiers, because of my blond hair and my blue eyes. Papa, Mama, and the boys, they all have the dark coloring and features of the Jews. Only I can pass for a Russian peasant.

And of course, as you know, Tovah, of all my family, only I can speak Russian without a Yiddish accent. Uncle Avrum calls it my “gift” for language. What kind of gift is this, Tovah?

The guard ran his greasy fingers through my curls. He smelled of herring and onion.

“Why aren’t you on your way to school?” he demanded.

My heart beat in my throat where my voice should have been. Mama is always saying my mouth is as big as the village well. Even you, Tovah, tell me I should not speak unless I have something to say. I know I talk too much. Yet as the guard played with my hair, fear silenced me.

“Who are you?” he asked. “What are you doing here?”

I forced myself to answer. I spoke in Russian, making my accent just like Katya’s, the peasant girl who comes to light our Sabbath fire.

“I’m here,” I said, “to take the train. My mother has found me work in a wealthy house.”

“You are young to leave home,” the rough-faced guard said, brushing the ends of my hair across his palm. “And such a pretty little thing.”

“That’s just what I told my mother,” I said. “But she insisted that I go anyway.”

The guard laughed. “Maybe you should stay in Berdichev. I might have better work for you here.”

“Maybe I will,” I said, looking into his rough, ugly face.

Papa did not tell me what to say to the guards. He simply said to distract them.

If it had been just the one guard, I might have occupied him until the train left the station.

Only there was another guard. He had a thin face and a straight back. His eyes were like the Teterev in the spring when the snow melts, churning with green ice. My curls did not interest him.

“Let her go,” the thin guard ordered. “Search the boxcars around and behind her.”

My heart banged in my throat.

I had to keep the guards away from my family until Uncle Avrum arrived from the factory. I prayed for Uncle Avrum to come soon.

Tovah, I tried to do what you are always telling me. I tried to be clever.

“You are in the army, aren’t you?” I said. “I know all about soldiers in the army.”

The guard with the eyes of green ice stared hard at me. “Tell me what you know,” he demanded.

“Well,” I said. “When I was nine, I saw some soldiers from Germany. Did you ever see those German soldiers?”

Both of the guards looked as if they remembered the Germans well.

“Those Germans came in airplanes,” I said. “So noisy, those planes.” I clasped my hands over my ears, banging myself with your book of Pushkin.

The stiff-backed guard glared at me.

“There was a German pilot,” I said. “A German pilot with a big potbelly. I wondered how he could fit in his plane; such a small plane, such a big German.”

The thin guard pivoted away from me. He squinted at something moving in the bushes across the train yard. Lifting his rifle, he aimed at the bushes and fired. Two birds rose noisily into the air.

I started talking faster.

“That German liked me pretty well,” I said. “He bought me candy and took me for walks. One day he put me in his plane and started the propeller. I didn’t like that, so I jumped out.”

I knew I was talking too fast. When I talked like this at home, Saul always got annoyed with me.

I couldn’t make myself slow down. The words came spilling out. If I could just keep them listening, they would run out of time to search the train.

“I jumped out of that fat German’s plane and landed in the mud,” I said. “And I ran home like the devil was chasing me. The German called for me to stop, but I wasn’t stopping for him. I—”

“Enough!” the thin guard commanded. “Enough of your chatter.” He pushed me aside and climbed into the freight car behind me. He sank his bayonet into the hay bales inside the car.

I asked the guard with the rough beard, “What is the problem? What is he looking for?” I tried to keep my voice from betraying my fear.

Suddenly the guard reappeared in the doorway to the freight car with my rucksack dangling from his bayonet. “What is this?”

I thought, If he finds Mama’s candlesticks in my rucksack, it is all over for my entire family. “I can’t go without my belongings, can I?” I said.

The two guards started arguing.

“Leave the girl alone,” said the one with the rough beard. “She’s a peasant, farmed out by her mother.”

The other narrowed his eyes. “She’s hiding something,” he said.

“What could she hide?”

The thin guard glared at me again. “This is very heavy for clothing,” he said, swinging my rucksack at the end of his bayonet. “What have you got in here?”

“What do you think?” said the guard with the rough face. “You think she’s hiding a Jew in her rucksack? You think she has something to do with the Nebrot boy? Look at her, listen to her. She’s no Jew.”

The other guard jumped down from the car, tossing my rucksack on the ground. My bag hit with a thud.

“What’s in there?” he asked again, preparing to rip my bag open with the razor-sharp blade of his bayonet.

“Books,” I said. “Like this one.” I held up your Pushkin, Tovah. “I like to read.”

The guard hesitated, staring into my face, but he did not rip open my rucksack. He started instead toward the next car, the car with Nathan inside. I did not know how to stop him.

That is when your father arrived, Tovah. It had taken him longer at the factory than he’d expected.

“Guards! Come here!” Uncle Avrum shouted from the woods.

The guards turned toward his voice. I turned too. The trees on either side of the road dwarfed Uncle Avrum. He stood short and round with his red beard brushing the front of his coat. I knew the smell of that coat.

He and Papa and Mama had planned for this. Mama had hoped not to involve your father, but Uncle

Avrum insisted on being part of the plan. He would make certain the guards suspected nothing. He said Papa could not let the fate of our entire family rest on the shoulders of a child.

I did not like when he talked about me that way last night, calling me a child. I felt insulted. Yet when I heard him call out to the guards this morning, all I felt was relief.

“Guards!” Uncle Avrum shouted again. “My factory. Someone broke into my factory.” He is a good actor, your father, in case you didn’t know.

The guards squinted their eyes against the morning sun. They recognized Uncle Avrum, but the thin guard did not want to help him.

“We must inspect this entire train before it leaves the station,” he said to the guard beside him. “That man is only a Jew. Why bother with the troubles of a Jew?”

The guard with the unshaven face hesitated. “We might get in trouble if we don’t help him. That’s Avrum Abromson. I once carried a message to him at his factory. He has important friends.”

“Come!” Uncle Avrum demanded. “Hurry! I haven’t got all day.”

I thought they would shoot Uncle Avrum for speaking to them in that way. They certainly would have shot Papa. But Uncle Avrum’s demand seemed to make up their minds to go with him. I knew your family had influence, Tovah, but I never realized how much. The guards left me by the train and headed across the clearing toward your father and his factory. I prayed Uncle Avrum had made the robbery look real so they would not suspect him.

The train whistle blew, once, twice, as the rough-bearded guard and Uncle Avrum disappeared up the road. The thin guard turned back toward me, looking for a moment as if he might change his mind and return to finish the inspection. Then he, too, vanished into the woods.

The train, straining on the tracks, moved a little backward before it started rolling forward, slowly, out of Berdichev.

You know what a good runner I am. I have learned to run to keep out of Saul’s reach. Outrunning the train was easy. I heaved my rucksack from the ground, tossing it into the boxcar. Stones skipped out from under my boots as I scrambled alongside, jumped on board, and, sprawling on my belly, pulled myself in.

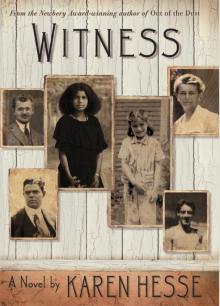

Witness

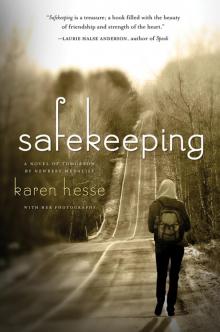

Witness Safekeeping

Safekeeping Sable

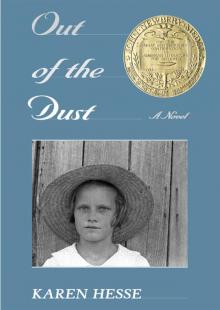

Sable Out of the Dust

Out of the Dust Letters From Rifka

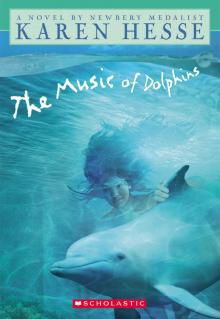

Letters From Rifka The Music of Dolphins

The Music of Dolphins Wish on a Unicorn

Wish on a Unicorn A Light in the Storm

A Light in the Storm