- Home

- Karen Hesse

Out of the Dust Page 7

Out of the Dust Read online

Page 7

and twisted rails,

scorched dirt, and

charred ties.

No one talks about fire

right to my face.

They can’t forget how fire changed my life.

But I hear them talking anyway.

April 1935

The Mail Train

They promised

through rain,

heat,

snow,

and gloom

but they never said anything about dust.

And so the mail got stuck

for hours,

for days,

on the Santa Fe

because mountains of dust

had blown over the tracks,

because blizzards of dust

blocked the way.

And all that time,

as the dust beat down on the cars,

a letter was waiting inside a mail bag.

A letter from Aunt Ellis, my father’s sister,

written just to me,

inviting me to live with her in Lubbock.

I want to get out of here,

but not to Aunt Ellis,

and not to Lubbock, Texas.

My father didn’t say much when I asked

what I should do.

“Let’s wait and see,”

he said.

What’s that supposed to mean?

April 1935

Migrants

We’ll be back when the rain comes,

they say,

pulling away with all they own,

straining the springs of their motor cars.

Don’t forget us.

And so they go,

fleeing the blowing dust,

fleeing the fields of brown-tipped wheat

barely ankle high,

and sparse as the hair on a dog’s belly.

We’ll be back, they say,

pulling away toward Texas,

Arkansas,

where they can rent a farm,

pull in enough cash,

maybe start again.

We’ll be back when it rains,

they say,

setting out with their bedsprings and mattresses,

their cookstoves and dishes,

their kitchen tables,

and their milk goats

tied to their running boards

in rickety cages,

setting out for

California,

where even though they say they’ll come back,

they just might stay

if what they hear about that place is true.

Don’t forget us, they say.

But there are so many leaving,

how can I remember them all?

April 1935

Blankets of Black

On the first clear day

we staggered out of our caves of dust

into the sunlight,

turning our faces to the big blue sky.

On the second clear day

we believed

the worst was over at last.

We flocked outside,

traded in town,

going to stores and coming out

only to find the air still clear

and gentle,

grateful for each easy breath.

On the third clear day

summer came in April

and the churches opened their arms to all comers

and all comers came.

After church,

folks headed for

picnics,

car trips. No one could stay inside.

My father and I argued about the funeral

of Grandma Lucas,

who truly was no relation.

But we ended up going anyway,

driving down the road in a procession to Texhoma.

Six miles out of town the air turned cold,

birds beat their wings

everywhere you looked,

whole flocks

dropping out of the sky,

crowding on fence posts.

I was sulking in the truck beside my father

when

heaven’s shadow crept across the plains,

a black cloud,

big and silent as Montana,

boiling on the horizon and

barreling toward us.

More birds tumbled from the sky

frantically keeping ahead of the dust.

We watched as the storm swallowed the light.

The sky turned from blue

to black,

night descended in an instant

and the dust was on us.

The wind screamed.

The blowing dirt ran

so thick

I couldn’t see the brim of my hat

as we plunged from the truck,

fleeing.

The dust swarmed

like it had never swarmed before.

My father groped for my hand,

pulled me away from the truck.

We ran,

a blind pitching toward the shelter of a small house,

almost invisible,

our hands tight together,

running toward the ghostly door,

pounding on it with desperation.

A woman opened her home to us,

all of us,

not just me and my father,

but the entire funeral procession,

and one after another,

we tumbled inside, gasping,

our lungs burning for want of air.

All the lamps were lit against the dark,

the house dazed by dust,

gazed weakly out.

The walls shook in the howling wind.

We helped tack up sheets on the windows and doors

to keep the dust down.

Cars and trucks

unable to go on,

their ignitions shorted out by the static electricity,

opened up and let out more passengers,

who stumbled for shelter.

One family came in

clutched together,

their pa, divining the path

with a long wooden rod.

If it hadn’t been for the company,

this storm would have broken us

completely,

broken us more thoroughly than

the plow had broken the Oklahoma sod,

more thoroughly than my burns

had broken the ease of my hands.

But for the sake of the crowd,

and the hospitality of the home that sheltered us,

we held on

and waited,

sitting or standing, breathing through wet cloths

as the fog of dust filled the room

and settled slowly over us.

When it let up a bit,

some went on to bury Grandma Lucas,

but my father and I,

we cleaned the thick layer of grime

off the truck,

pulled out of the procession and headed on home,

creeping slowly along the dust-mounded road.

When we got back,

we found the barn half covered in dunes,

I couldn’t tell which rise of dust was Ma and

Franklin’s grave.

The front door hung open,

blown in by the wind.

Dust lay two feet deep in ripply waves

across the parlor floor,

dust blanketed the cookstove,

the icebox,

the kitchen chairs,

everything deep in dust.

And the piano …

buried in dust.

While I started to shovel,

my father went out to the barn.

He came back, and when I asked, he said

the animals

weren’t good,

and the tractor was dusted out,

and I said, “It’s a

wonder

the truck got us home.”

I should have held my tongue.

When he tried starting the truck again,

it wouldn’t turn over.

April 1935

The Visit

Mad Dog came by

to see how we made out

after the duster.

He didn’t come to court me.

I didn’t think he had.

We visited more than an hour.

The sky cleared enough to see Black Mesa.

I showed him my father’s pond.

Mad Dog said he was going to Amarillo,

to sing, on the radio,

and if he sang good enough,

they might give him a job there.

“You’d leave the farm?” I asked.

He nodded.

“You’d leave school?”

He shrugged.

Mad Dog scooped a handful of dust,

like a boy in a sandpit.

He said, “I love this land,

no matter what.”

I looked at his hands.

They were scarless.

Mad Dog stayed longer than he planned.

He ran down the road

back to his father’s farm when he realized the time.

Dust rose each place his foot fell,

leaving a trace of him

long after he’d gone.

April 1935

Freak Show

The fellow from Canada,

James Kingsbury,

photographer from the Toronto Star,

way up there in Ontario,

the man who took the first pictures of

the Dionne Quintuplets,

left his homeland and

came to Joyce City

looking for some other piece of

oddness,

hoping to photograph the drought

and the dust storms

and

he did

with the help of Bill Rotterdaw

and Handy Poole,

who took him to the sandiest farms and

showed off the boniest cattle in the county.

Mr. Kingsbury’s pictures of those Dionne babies

got them famous,

but it also got them taken from their

mother and father

and put on display

like a freak show,

like a tent full of two-headed calves.

Now I’m wondering

what will happen to us

after he finishes taking pictures of our dust.

April 1935

Help from Uncle Sam

The government

is lending us money

to keep the farm going,

money to buy seed,

feed loans for our cow,

for our mule,

for the chickens still alive and the hog,

as well as a little bit of feed

for us.

My father was worried about

paying back,

because of what Ma had said,

but Mrs. Love,

the lady from FERA,

assured him he didn’t need to pay a single cent

until the crops came in,

and if the crops never came, then he wouldn’t pay a

thing.

So my father said

okay.

Anything to keep going.

He put the paperwork on the shelf,

beside Ma’s book of poetry

and the invitation from Aunt Ellis.

He just keeps that invitation from her,

glowering down at me from the shelf above the piano.

April 1935

Let Down

I was invited to graduation,

to play the piano.

I couldn’t play.

It had been too long.

My hands wouldn’t work.

I just sat on the piano bench,

staring down at the keys.

Everyone waited.

When the silence went on so long

folks started to whisper,

Arley Wanderdale lowered his head and

Miss Freeland started to cry.

I don’t know,

I let them down.

I didn’t cry.

Too stubborn.

I got up and walked off the stage.

I thought maybe if my father ever went to Doc Rice

to do something about the spots on his skin,

Doc could check my hands too,

tell me what to do about them.

But my father isn’t going to Doc Rice,

and now

I think we’re both turning to dust.

May 1935

Hope

It started out as snow,

oh,

big flakes

floating

softly,

catching on my sweater,

lacy on the edges of my sleeves.

Snow covered the dust,

softened the

fences,

soothed the parched lips

of the land.

And then it changed,

halfway between snow and rain,

sleet,

glazing the earth.

Until at last

it slipped into rain,

light as mist.

It was the kindest

kind of rain

that fell.

Soft and then a little heavier,

helping along

what had already fallen

into the

hard-pan

earth

until it

rained,

steady as a good friend

who walks beside you,

not getting in your way,

staying with you through a hard time.

And because the rain came

so patient and slow at first,

and built up strength as the earth

remembered how to yield,

instead of washing off,

the water slid in,

into the dying ground

and softened its stubborn pride,

and eased it back toward life.

And then,

just when we thought it would end,

after three such gentle days,

the rain

came

slamming down,

tons of it,

soaking into the ready earth

to the primed and greedy earth,

and soaking deep.

It kept coming,

thunder booming,

lightning

kicking,

dancing from the heavens

down to the prairie,

and my father

dancing with it,

dancing outside in the drenching night

with the gutters racing,

with the earth puddled and pleased,

with my father’s near-finished pond filling.

When the rain stopped,

my father splashed out to the barn,

and spent

two days and two nights

cleaning dust out of his tractor,

until he got it running again.

In the dark, headlights shining,

he idled toward the freshened fields,

certain the grass would grow again,

certain the weeds would grow again,

certain the wheat would grow again too.

May 1935

The Rain’s Gift

The rain

has brought back some grass

and the ranchers

have put away the

feed cake

and sent their cattle

out to graze.

Joe De La Flor

is singing in his saddle again.

May 1935

Hope Smothered

While I washed up dinner dishes in the pan,

; the wind came from the west

bringing—

dust.

I’d just stripped all the gummed tape from the

windows.

Now I’ve got dust all over the clean dishes.

I can hardly make myself

get started cleaning again.

Mrs. Love is taking applications

for boys to do CCC work.

Any boy between eighteen and twenty-eight can join.

I’m too young

and the wrong sex

but what I wouldn’t give to be

working for the CCC

somewhere far from here,

out of the dust.

May 1935

Sunday Afternoon at the Amarillo Hotel

Everybody gathered at

the Joyce City Hardware and Furniture Company

on Sunday

to hear Mad Dog Craddock

sing on WDAG

from the Amarillo Hotel.

They hooked up speakers

and the sweet sound

of Mad Dog’s voice

filled the creaky aisles.

Arley Wanderdale was in Amarillo with Mad Dog,

singing and playing the piano,

and the Black Mesa Boys were there

too.

I ached for not being there with them.

But there was nothing more most folks in Joyce City

wanted to do

than spend a half hour

leaning on counters,

sitting on stairs,

resting in chairs,

staring at the hardware

and the tableware,

listening to hometown boys

making big-time music

on the radio.

They kept time in the aisles,

hooting after each number,

and when Mad Dog finished his last song, they sent

the dust swirling,

cheering and whooping,

patting each other on the back,

as if they’d been featured

on WDAG themselves.

I tried cheering for Mad Dog with everyone else,

but my throat

felt like a trap had

snapped down on it.

That Mad Dog, he didn’t have

a thing to worry about.

He sang good, all right.

He’ll go far as he wants.

May 1935

Baby

Funny thing about babies.

Ma died having one,

the Lindberghs said good night to one and lost it,

and somebody

last Saturday

decided to

give one away.

Reverend Bingham says

that Harley Madden

was sweeping the dust out of church,

shining things up for Sunday service,

when he swept himself up to a package

on the north front steps.

He knelt,

studying the parcel,

and called to Reverend Bingham,

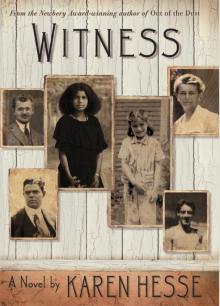

Witness

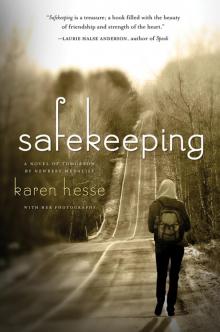

Witness Safekeeping

Safekeeping Sable

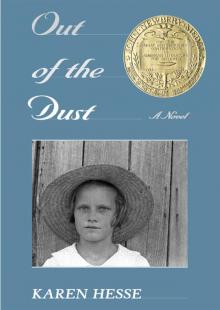

Sable Out of the Dust

Out of the Dust Letters From Rifka

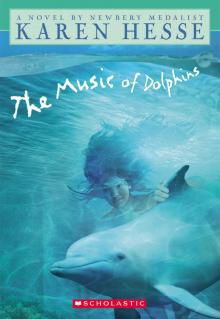

Letters From Rifka The Music of Dolphins

The Music of Dolphins Wish on a Unicorn

Wish on a Unicorn A Light in the Storm

A Light in the Storm