- Home

- Karen Hesse

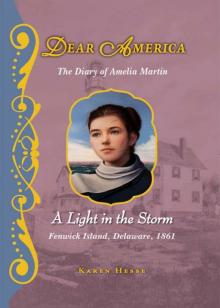

A Light in the Storm Page 6

A Light in the Storm Read online

Page 6

My mind goes like this, in circles, angry at the North because they stubbornly corner the South, angry at the South because they pigheadedly challenge the North. Angry at my father because he has given up everything for his lofty principles. Angry at my mother because she cannot love him in spite of those principles.

This afternoon I lashed out at Mother when she ordered me to wash her underthings. And then I looked at her face, saw the pain in her eyes. And I knew suddenly what it cost her to ask me to do such a chore for her. Then I grew angry at myself.

Grandmother isn’t well, either. I gave her rum to ease her aches. Rum is what she prefers. I did her heavy and light cleaning and asked Dr. McCabe to look in on her.

Seeing my stormy mood this afternoon, Uncle Edward searched for the words to cheer me. He told me not to brood about the War.

But how can I not brood?

Daniel came to see me last night to say good-bye. This time, when I heard the footstep on the stair, I knew it would be Daniel’s face coming through the watch room door. And then he was there, his eyes shining, his fine frame proud and straight. He held me only a moment. “Good-bye, Amelia,” he whispered in my ear. “Wait for me.”

Then he was gone.

Thursday, May 23, 1861

Fair. Wind E. Moderate.

The fishing is the best I can remember. Rowed my catch to shore this morning and sold it in Bayville. Uncle Edward got first choice. Brought the rest to sell at the hotel. The additional money eases Mother’s fretting. Mother always loved to look fashionable. She has not picked out new cloth for over six months, except perhaps for the aprons she made me at Christmas. She is unable to sew now anyway because of the swelling in her fingers.

School ends tomorrow. Mr. Warner urged me to keep up with my reading and made a gift to me of several history books from his own collection. I shall miss Mr. Warner. I hope he fares well.

Uncle Edward said that oat and wheat crops have recovered exceedingly well from the unseasonable cold earlier this month. The yield promises to be heavy. Perhaps this will help keep the Union army fed.

The Delaware Regiment is assembling. Daniel is on the march.

Thursday, May 30, 1861

Clear. Wind S.E. Moderate.

Daniel’s regiment is encamped one mile from Wilmington. I hope he is getting enough to eat. I hope his feet don’t hurt. I hope that he is able to stay dry and sleep well.

The Stars and Stripes fly over Uncle Edward’s store, though I see the flag nowhere else in town except at the post office and at school.

Traded my fish today for strawberries, which are large and ripe and sweeter than wild honey.

Wish I could share them with Daniel. Instead I brought them back home and made shortcake for Father and Keeper Dunne.

Mother has lost interest in sweets. She has lost interest in most everything.

I fear this will not be a fast war. The Government is looking for more men. Men to fight for three years rather than three months. Father mumbles to himself. I overheard him this morning as he rubbed lamp rouge into the reflectors. Will he try enlisting?

If Father enlists in the Union army, that will push Mother away from him forever.

Thursday, June 6, 1861

Cloudy. Wind N.E. Fresh.

Uncle Edward has had word from his friend Warren Harris, who shipped out last August for Buenos Ayres on The Pride of the Ocean. Mr. Harris’s ship had been at sea since before Mr. Lincoln’s election and the unhappy events that have followed. Her crew had no knowledge that we had become, in their absence, a country at war with itself.

Warren Harris wrote Uncle Edward that when The Pride of the Ocean pulled into Apalachicola, in Florida, she was boarded by privateers under letters of marque issued by Jefferson Davis. The captain and crew, including Mr. Harris, were taken prisoner and kept for over a week in a room without furniture or bedding, and fed only rice and water. With the help of the National Government, the captain and crew were at last able to regain their ship, but the privateers had stripped it of everything movable, including all clothing and food, except for a supply of rice for the trip back home to Boston. Those privateers are as thorough as Oda Lee. Uncle Edward said Mr. Harris’s captain was lucky to get away with his ship. I think Uncle Edward is right.

As I write this on my watch, I look out toward the sea. Day and night, there are increased sightings of ships moving from North to South. Our log is filled with sightings and we must be ever watchful for signs of trouble. To see so much movement on the water excites me, but it also fills me with fear. Those ships are carrying boys as beloved to someone as Daniel is to me.

I purchased a copy of The Soldier’s Companion in Bayville today for 25 cents and sent it to Daniel so he might know I am thinking of him.

Sunday, June 9, 1861

Rain. Wind S. Fresh.

Keeper Dunne led us in prayer.

Caught a feast of crabs. It felt good, out on the water, the rain falling softly.

Now I stand watch.

This war between neighbors means nothing to the sea. It is a very good lesson.

Thursday, June 13, 1861

Cloudy and Fog. Wind S.W. Light.

The shoals are shrouded in fog and we have kept the Light burning all day.

So far, no wrecks. Oda Lee sits like a cormorant out on the rocks, waiting for trouble. I cannot see her now. But I believe she is there still.

Mrs. Worthington had word from Daniel yesterday. His company left its encampment last Sunday, along with the other five companies in the Delaware Regiment.

Daniel will go to Maryland now. Three months is not so long.

I visit Mrs. Worthington every day. Today I helped her pack a box of letter paper, envelopes, stamps, soap, and towels for Daniel. Being with his family, in his rooms, brings Daniel into my heart so that I can imagine him right beside me; I can almost smell him sometimes. Perhaps I miss him a little more when I am there. But I am still happy to be there, to be useful in Daniel’s home.

Uncle Edward had news of a battle near Norfolk, Virginia. Two Federal regiments fired upon each other by mistake, killing two boys. Then the Federal troops united, only to be attacked by a rebel battery. Is it possible that thirty to forty Federal boys lost their lives, and nearly one hundred more were wounded?

The Government says the troops in the field, the three-month volunteers, shall be paid for their duty. This will ease Daniel’s mind, and Mrs. Worthington’s. Now, in addition to the pay for duty, the Government offers a $100 bounty if the three-monthers will enlist for three years before they are mustered out of service. Daniel’s mother could live well on $100. But I wish Daniel would not sign on for so long. What if the War actually lasts three years?

When I stopped for the mail, there was a letter for me, from Daniel! I made myself wait until I could be alone here, in the Light, to read it.

Daniel’s letter is most polite. But in one paragraph I see a flash of the Daniel I have come to know so well. This paragraph I shall copy out.

The health of the camp is good. The men are merry and happy as men can be. We have just enough work to make us relish sport. Target-firing, fishing, bathing, quoits, newspapers, &c fill up the time between drills and guard duty. At night all the noises of the barnyard can be heard from the quarters of Company D. Such crowing, Amelia, and cackling, and grunting, and bellowing were never surpassed by any living animals. The Kent boys are gaining a reputation of being great cooks. We have our batch of hot bread daily. It is not as good as your pie, nor my mother’s duck, but it is mighty good anyway.

Thursday, June 20, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind S.W. Moderate.

Mother is not interested in the garden this year. Where last year she supervised me in the planting and weeding, this year I alone tend the roses, the turnips, the tomatoes, and cucumbers.

I do not mind the extra work, particularly now that school is out. It does not take much to tend this sandy garden. I am able to keep it weeded and watered. I love working

in the garden. It holds me out of doors for hours with the wind and the smell of the sea and the sound of the breakers singing in my ears.

Why can it not be the same for Mother? Why can’t the sea bring her the peace it brings me?

Friday, June 21, 1861

Clear. Wind S.W. Light.

Dr. McCabe’s brother came into Uncle Edward’s store while I was there today. He has known almost a week now about his son, who was killed in Maryland while on guard at the railroad bridge over the Big Elk. Dr. McCabe’s nephew was killed by an oncoming train. His body will be returning to Delaware any day now. The McCabe family had hoped he would be home soon. But not like this.

Saturday, June 22, 1861

Rain and Fog. Wind S.E. Light.

We are having a fine fall of rain. The heavy clouds and sheeting downpour kept Father, Keeper Dunne, and me busy all day and now into the night on fog shift at the Light. The log is filled with entries recording wind, conditions, behavior of the lamps, &c. The bell-buoy boat, repaired and freshly painted, clangs out its warning. Mother has kept to her bed with the curtains drawn and the windows shut.

Tuesday, June 25, 1861

Rain and Fog. Wind S.E. Light.

I cannot explain how I knew a ship had gone aground on the sandbar last night during my watch. I could not see it. And yet I felt it like a scraping inside me.

I’d been watching the lights of passing ships the best I could, but the fog made tracking nearly impossible. The crew of the yacht did not hear the bell-buoy boat ringing its warning.

I hesitated to wake Father and Keeper Dunne. I had no proof that anything was amiss. Just a “feeling.” I hesitated, also, to bother Mother unnecessarily.

Standing out on the balcony, the rain slashing against my face, I thrust my head toward the sea and listened. It was then I heard the shouts of men and a faint sound, a ghostly sound, like a woman crying from the depths of the sea.

This time I did not hesitate. I rang the alarm bell and within minutes Father and Keeper Dunne joined me.

When their hearts and their breathing stilled enough, they heard, too, the cry of terror from a woman, the calls for help from deep-voiced men.

Keeper Dunne and Father rowed out toward the sound. Fortunately the waves were not high and they did not have to fight anything more than the fog and the rain. But I could hear the cries of panic increase as the pleasure yacht slowly gave way and slipped under the water.

Father and Keeper Dunne brought back the four crew members and all five of the passengers, including the woman I had heard. She wept softly as Father helped her up the beach to the house. I could see the lamp burning upstairs in the kitchen window. Mother could be counted on even in her sad condition. She cared for our unexpected guests through the night until this noon, when they were all questioned by the insurance company and returned to the mainland.

Last night, after all the members of the sailing party, their crew, Father, and Keeper Dunne had disappeared inside the house, a deadly quiet settled back over the Light. The sea hardly moved. Nothing moved.

Until I saw the lantern. Oda Lee, floating through the fog, seeing if there was anything left to scavenge.

Thursday, June 27, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind S.E. Moderate.

Uncle Edward said today that several of the area farmers are arranging to take a day off for observation of the Fourth. This is not an easy time for them to be away from their fields. Both the hay and wheat are heavy and ready for the scythe. Yet for these men it is important to show their loyalty. I am so glad to know of them.

Daisy has gone off to Pennsylvania for a week and Uncle Edward asked if Father and Mother and I might like to come across the Ditch this evening and share a meal with him. I rowed back excitedly and asked, but Keeper Dunne had other plans and could not let both of us go. I suggested that Mother and I could go without Father. Perhaps we could bring Grandmother to Uncle Edward’s with us. Mother hesitated. I could see how much she longed to get off the island and see Grandmother. But she had kept to her bed most of the day because of the swelling in her joints. In the end she did not think she could bear the motion of the boat across the Ditch.

The only thing that keeps my spirits buoyed is this letter I received from Daniel.

Here I am in Maryland, a high private in the U. S. army, a place a few weeks ago I had no expectation of seeing. I had hoped to make it at least to Washington but rumor has it the Government isn’t sure it can trust those of us from Delaware.

We are getting along very well on the feed we get. Hard crackers and salt pork are not the most palatable viands, but I remember, Amelia, how you told me of the sufferings of our Revolutionary sires, and I am careful not to complain. You and your great mind full of history, you take all the fun out of being miserable.

Our victuals are not set before us by servants, or by a sister or mother, I assure you. We wash our own dishes, and, for that matter, sometimes our own clothes. Ah well, I am happy, for I am here for my country’s sake.

Our Sundays are not spent here as at home. That day is like all others to us. Plenty of drill and very little church.

The floors on which we lie are made of peculiarly hard wood—not a soft plank to be found. All the better, it will accustom me to hardships. But what a fall it is from a comfortable bedstead and mattress. Never mind. If I had to fall in this life, at least I did not fall from the barrel at the top of your Lighthouse.

The sights of Maryland are not so different from our own state, though there are places from history that might interest you. As for me, I wish I could be back in Bayville for a few hours. Here we are surrounded by men, no ladies’ society whatsoever. It is hard to imagine I ever looked for an excuse to leave my sisters and mother in that gracious house of women. I am afraid, with respect to my present companions, I will become a regular bear and lose all my refinement—that is, if I ever had any.

I cannot help but smile, even as I copy this. Bless Daniel. To make me smile at such a time.

Thursday, July 4, 1861

Clear. Wind S.W. Fresh.

Last night, I kept an even more careful watch than usual as all through the night the crack of pistols and guns could be heard across the Ditch, announcing the arrival of our country’s Independence Day. It was all in good fun, but my ear listened to every noise, lest it warn of danger and duty. The firing of guns may mask another sound that would tell of disaster on the shoals. Fortunately no such disaster occurred through the night. At sunrise the church bells rang.

Father and I cleaned and polished the big panels of bull’s-eyes and prisms in the lantern room as quickly as possible so we could get a start on the day.

I asked Mother last evening if she would accompany us to the Fourth of July program in Lewes and she agreed. But when she woke this morning, she found it a particularly bad day. She urged us to go on without her. Keeper Dunne agreed to look in on her from time to time.

Mother’s hand trembled when I came to say good-bye, but she said I must not be concerned. I must have a lovely day.

Uncle Edward had posted a notice that his shop would be closed. Daisy has not yet returned from Pennsylvania.

We arrived by wagon in Lewes just before ten, in time to watch the long procession of clergymen, orators, choirs, committees, cadets, citizens on foot, citizens on horseback, citizens in carriages, and a company of guards. Two large American flags draped the archway under which the orators spoke. Evergreens and flowers festooned the whole platform. The Reverend prayed for our country, for a happy issue out of its present difficulties, for a pardon of our individual and national sins, and a blessing upon the troops defending our liberties. The Declaration of Independence was read and more speakers addressed the crowd.

Late afternoon, Father and I left Uncle Edward off in Bayville, returning to the island in time to light the lantern. I regretted we could not stay in Lewes for the fireworks, but as I walked out on the narrow gallery, I saw the displays of brilliant lights at sea and on land.

Sunday, July 7, 1861

Fair. Wind S.E. Moderate.

President Lincoln is calling for 400,000 more men.

Tuesday, July 9, 1861

P. Cloudy. Wind S.E. Light.

General Scott says, “Make haste slowly.”

It is advice that works equally well at a lighthouse.

Thursday, July 11, 1861

Clear to Rain. Wind S.E. to N.W. Moderate.

Grandmother wanted to gossip when I came to do her chores. She said that Ann Blackiston has left her husband, and he has posted notices every-where that he will not be responsible for any charges she contracts. I beat the rugs ruthlessly from the porch and weeded Grandmother’s flower beds in the rain. But I could not escape the fact that wives leave husbands, husbands leave wives. If a country can break its bonds, why not two people?

But Mother and Father must reconcile. When a storm comes, everyone is needed to run the Lighthouse station. Father, Mother, and I work together alongside Keeper Dunne, each with our own tasks, to meet the storm head on, and to survive it. And might not another country act like a storm? What if England, or France, or Spain decides we are weak now? It would be easy for them to come blustering in and conquer us.

I feel as if I am the Light in my family. I must keep my hope burning, so that Father and Mother, even in the darkness that seems to engulf them, might find their way back.

Monday, July 15, 1861

Clear. Wind S.E. Fresh.

A comet appeared recently in remarkable brilliancy, although now it is fading. It is called Thatcher’s comet, after the man who discovered it last April. But everyone calls it the “war comet.” Every night, after my watch, I go out and sit on the beach and send up my troubles to it.

Witness

Witness Safekeeping

Safekeeping Sable

Sable Out of the Dust

Out of the Dust Letters From Rifka

Letters From Rifka The Music of Dolphins

The Music of Dolphins Wish on a Unicorn

Wish on a Unicorn A Light in the Storm

A Light in the Storm