- Home

- Karen Hesse

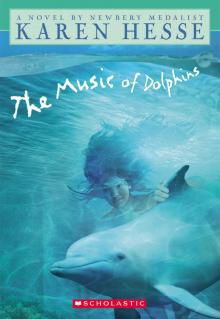

The Music of Dolphins Page 3

The Music of Dolphins Read online

Page 3

There is no mother here. I am lost.

I feel bad, but not too bad.

Today I am in my own bed in my room at the house by the river. I am getting better.

Doctor Troy brings Shay to visit.

Shay stands by my bed, but she looks at the wall.

I take her hand.

I ask, Why, Shay, why do you look at the wall?

Shay does not answer.

The eyes of Shay are empty.

Where is Shay? I ask. Shay is not inside here.

I stroke the hand of Shay. I stroke the face of Shay. Shay, come back.

And she does. A little. I feel the push of her cheek into my open hand.

Doctor Troy says, Shay wants to do good work, but the work is so hard for her. She likes it best when you help her, Mila.

Doctor Beck says it is time for you to rest, Mila. Shay must go.

Shay holds my hand very hard.

Doctor Troy says, Say good-bye to Mila, Shay.

He opens the hand of Shay, one finger, then one finger, then one finger, and takes the little hand of Shay.

Together they walk out of my room.

I put on the warm clothes. I walk with Sandy. We cross the big street and go to the river. I know now the river is not a place for me to swim.

I see many houses on the bank of the river. From one house there is music. I say, Can we go to that house?

Sandy says, No. She says, We don’t know the people who live there. You can’t just go anywhere you wish, Mila. No person can come on the land of another without permission.

In the sea we go where we wish. We eat what we wish. We swim and play together in the big sea. Families of dolphin come together, from the cold sea, from the warm sea, from the deep sea and the cays. We play and sleep and eat together. We fight only the hungry ones who like to eat us. Sometimes the boy dolphin is pushing a girl dolphin. But most of the time the dolphins are so good with other dolphins. And we are going everywhere in the sea.

Sandy says, What about territory? Do dolphins have territory?

I ask, What is territory?

Sandy says, Territory is a place where you belong, a place belonging to you.

I think she means the place we like to go best. But we are not told we can go only there. We go there because we like to go there. No other reason. We share the good places with all who come.

I feel sad for humans. Humans go only where it is permission. In the sea there are no locks or switches, no doors or walls.

Sometimes there are nets. Nets are death to dolphins. Nets are like walls in the sea.

Sandy is my friend. She is worried.

I say not to worry. I am so happy. I love the lessons. I love my work with the computer. With the cards. With the paper and crayons and pencils and paint. We dance. We sing. We go different places. We swim. We play games. We have a good time all day. And I am so happy to be with Shay. I want Shay to make progress.

I sit on the classroom floor with Shay. I play a song on the recorder for her. Not a big song. Just three notes put together in a little pattern. I play it over and over. I play it soft for Shay. I play it loud for Shay. I put the recorder on the cheek of Shay and play very, very gentle. I hold the notes, and I can feel them rubbing against each other inside the recorder and inside me.

Listen, Shay, I say, and I face her with my recorder. I play so that the hair on the head of Shay lifts and falls with each note, so softly, like the wings of the ray flying through the slow green water.

I feel the music inside me. It says something more than just the notes, more than just the sounds. It is hearing with more than the ears.

Like the way it is when I am with the dolphins. Or when I see Justin and Doctor Beck together. Or when Sandy talks about her father who is dead. There is a way I feel when Sandy hugs me so good and long and her stiff hair brushes my ear and her good smell fills my nose.

The music makes these different feelings inside me, too.

Shay stands and hops around the classroom. She is making a funny kind of singing all by herself. It is a little, little thing like my three-note song on the recorder, but it makes Doctor Beck and Sandy and Doctor Troy happy. It makes me happy too.

I can play five notes on the recorder. With those notes I can make many, many songs. It is not big music like the music Sandy gives me to put in the tape machine, it is not the music of Mozart, but my teacher, Doctor Peach, says if I can play these songs, I can play songs more harder in a little time.

I have to learn many notes before I can make music like Mozart. I want to play the recorder day and night. When I am not playing, I feel a tightness inside me, like when the sea grass catches my feet and I cannot break free. All around me swims the big music, but I am trapped inside the sea grass of my little notes.

Sandy is helping with my journal. My journal is this writing I do on the computer. Sandy shows me how much I learned in this year. She says when she first saw me, I knew five words. Now I know many words. But many words I do not know. And sometimes I make mistakes with the words I do know.

Doctor Beck makes more games for me to play. Other doctors come too. I like to play their games. When I understand what the doctors want, I am happy to do it. It makes the doctors happy too. I like to make the doctors happy too. Shay does not like the games so much. I help her. I show her how to play.

Shay sits on the floor. She looks at the wall. I see a look of lost in her eyes. I stroke the hair of Shay. I talk to Shay sometimes in dolphin, with my nose sound. Shay laughs at dolphin talk. I want to make Shay laugh all the time. But Doctor Beck says to make only human talk with her. So she can learn.

Shay is not happy. She can make only a little talk. One word. One word. One word.

Sandy says Shay never laughed before I came. Sandy says I am very smart to make Shay laugh with my dolphin talk. In the beginning, I did not make dolphin talk for Shay to laugh. I thought Shay understood dolphin talk. I thought Shay was like me. But Shay was not understanding dolphin talk, because I was not saying funny things and still Shay was laughing. So I know she is laughing because dolphin talk makes in her ears something funny. I love the sound of Shay laughing.

There is so much laughing in my dolphin family. Inside laugh. Outside laugh. I laugh with Sandy, but I miss dolphin laughing. I ask, Sandy, do you have a tape of dolphin laughing?

Sandy says no, but she will look for this tape.

Justin brings me a radio.

He says, This is old. My father sent me a new one. You can have this.

Justin shows me to fit the plug in the little wall holes.

You turn it on here, he says. And move the knob to tune the stations.

Justin shows me where to put my hand.

I turn the radio off and on. If I move the knob so slow, I can find music, so much hiding in the radio. If I turn the knob and turn the knob, I can find so many different sounds. So many different voices. There is so much inside the radio. And it is all human.

I know seven notes on the recorder now. G-A-B-C-D-F-E. I play so many songs. They go up a little, down a little, like small waves on a calm day. It makes me happy to play the songs again and again.

Doctor Beck and the other doctors make the games hard for me. They say I learn fast. They say I can catch up with others my age before too long. Good. I want to catch up. I want to be with others.

I chase Shay around outside, the way I chased my dolphin cousins. But Shay stands in one place and I catch her too easy. Shay drops to the ground. She does not like when I move fast.

I throw Shay a ball, very gentle. She does not put her hands out to catch it. I put the ball in her hands. She drops it. She has two good hands. My dolphin family, they would like to have the hands of Shay.

Shay uses her hands to eat. Only to eat.

I love to use my hands. To play the games, to make the music on the recorder. To make the machine with the tapes play. To bring the music from the radio. To make the computer say the words I am thinking. I like every li

ttle thing I am learning with my fingers and my toes.

Sandy has a bag in her hand. In the bag she has many books. I like books, but you cannot read them in the water. Yesterday I took one book with me in the bath and the book looked very bad after. I am learning. Some things can go in the water, like my dolphin boots, but other things, like books, are not so good when they get wet.

Sandy says, Remember, Mila. Don’t go swimming with these.

Sandy thinks I need help to remember, but I remember many things.

Sometimes I even remember a little before the dolphin time. I remember sitting on the knees of a woman. I remember a game of riding her knees.

I am drawing for Sandy a picture of riding the knees.

I ask, Does Shay remember the time before Doctor Troy and Doctor Beck?

Sandy says it is hard to know. The mother of Shay did not talk to her. She kept Shay in a little room all day, all night. For Shay it was always dark.

I miss the bright light of the ocean, the good bright light of dolphin time. I am too sad to think of Shay always in the dark.

And in the sea, a dolphin mother always is making certain her baby is good. A dolphin aunt is always near to help. The baby has food to eat, sometimes the thick fishy milk from the dolphin mother, sometimes the sweet fish fresh from the sea. The baby is protected when a shark comes. Where is the good mother to protect Shay?

Doctor Beck says not all humans are good. She says, Even good humans are not good all the time, Mila. But most humans want to be good. Doctor Beck asks, Are all dolphins good?

I do not know how to answer this.

I ask Doctor Beck, Tell me what it means to be good.

My question makes Doctor Beck tired. I see it in her hands. I see it when she moves.

Doctor Beck says, Good is honest, good is fair, good is doing what is right.

I think dolphins are good. Not all of the time, but most of the time. Maybe dolphins are not so different from humans.

Doctor Beck is happy today. She says, Mila, your journal is very beautiful. Very important. She says my writing is good science. Doctor Beck asks me to write about my time in the sea. She wants to know dolphin life. She wants to learn dolphin talk! She says to know these things will be a most important learning for people.

I look at Doctor Beck.

For one moment, she makes me think of the orca who is so big and strong and beautiful, and so dangerous when he is hungry. I think for one moment that Doctor Beck is hungry to eat me. Then I think, Doctor Beck is not an orca.

Doctor Beck, I say. Dolphin knowing is so big. I do not have all the outside words to tell you. But Doctor Beck wants to know very strong about the dolphin time. If you could teach us what you’ve learned, Mila … there is nothing more important you could do.

I come from the sea. I come from the deep tons, from the ringing bubbles, from the clicking claws and rolling tides. I come from the many winds of the sea, from the place between sky and deep where the gulls cry and the waves shift under the bright eye of the sun. On clear nights the round moon leans across the sea. Its arm stretches, scooping water. The moon paints a stripe of light. My dolphin mother swims in the path of the moon. I am not like her. I have hands at the ends of my arms, fingers at the ends of my hands. My fingers open and close. With them I do things the others cannot. I am not like the others. I have feet. I can walk on land. The dolphin moves like light. The dolphin flies through the wet breath of the sea. I cannot swim the quiet stroke of the dolphin. I cannot hear the whole sound, though it sings through me.

Each morning I swim out to them. We brush through the water, feeding, playing, singing, resting, dancing in the rolling waves, racing from storms, racing for the joy of moving with the water slipping over our backs, with the water sliding under our chins. The water opens, and we dive in through the wild paths of the sea.

In the sea there is always play. Anything and everything is to chase and catch and toss and taste and drag. There are near crashes and laughter, dolphin laughter, sparkling like a thousand drops of sunlight. My dolphin cousins play with me gently. I am so little beside them. They know me inside and out. I lick my lips as they send their humming through me. I never tire of the thrill as they slide up under my fingers or I glide down over their flukes.

At birth times, I can sense the change, the humming aimed at one, and all of us begin the wait. It is exciting, the waiting before a calf is born. The squeaks, the creaks and clickings, the chirps and whistles. Nothing is the same as we wait with the waiting mother. She bends and stretches, bends and stretches. She claps her flukes against ocean swells and the sound travels through my bones.

We wait for new life to slip, tail first, into the big sea.

I watch the others, seeing, hearing, feeling what they feel. My dolphin mother touches me, one stroke of her flipper, telling me when it is time.

Sinking below the surface, eyes open, I see there, in a cloud of pink, a tail, then a body and head, coming from the slit in the underbelly of the mother.

A quick spin and the cord snaps and slowly, what is not dolphin, what is not calf, mixes with the sea and drifts down through the deep blue. And what is left is a new cousin.

The mother guides it to the surface, but the calf knows what to do, and breaking through to the air takes a first gasp through the top of its head.

The calf is wrinkled from being folded inside its mother, its tail curls like an underwater weed, opening slowly with the gentle tug of the tide.

The calf bumps against its mother, searching.

The mother studies her calf, stroking it. They nuzzle, skin to skin. The mother hums, sounding her baby, inside and out, while the calf pokes its new self along the length of its mother, until the mother rolls on her side and the calf finds milk, a great stream of thick, sweet milk, rushing reward for the pressure of lips.

Sometimes the birth does not go right and the baby dies. And then the mother lifts her silent calf to the air, but there is no calf there, only an empty body, and the mother tells a story, about this thing that happened, and the others join in telling their parts, and the story grows for days and days until the mother is ready to let the baby go.

When I came, in a storm, my dolphin mother had given birth. Her dolphin baby did not blow and did not blow. Tenderly, she let her dead calf go, and reached for me.

She stood the storm, the sharp rain stinging her hide; she carried me, alive, through the giant swells to the cay, where I woke the next day to a calmer sea, and a warming sun, and a new life.

When I was so little and hungry, my dolphin mother stroked me and, leaving her white underside showing there above her flukes, she gave me her milk.

I gulped and choked, gulped and choked, gulped and swallowed and choked some more, but swallowed enough to grow strong and stronger and finally fat and warm on the fishy richness of dolphin milk.

Each day my dolphin family dives for fish, I stay swimming above. Sometimes I swim a little away.

When my aunt catches me, she claps her jaw, slaps water at me with her tail. But I need to always move in the deep water. I drift away from my aunt, floating between the new mothers and their calves. The tingle of their soundings passes through me.

My dolphin mother returns, a fish sideways in her mouth. She locks down with her pointed teeth and the tail and head fall away, down, down through the darkness. She flips out a fish for me to eat. I take the fish in my hands, my good hands for stroking dolphin backs, for holding, and tearing, and throwing, and pulling. I catch the fish in my good hands and tear into its sweet flesh with my teeth.

In the night, things rise from the deep. They rise with their long arms, with their sharp beaks, with their strong suckers to pull me under and hold me until I have no breath. I struggle in a blinding cave of pain. My dolphin mother hears and comes, ramming the monster that holds me, and the others ram it too. They batter and bang the beast until I am free, then carry me near shore, where I crawl onto the sand and remember to breathe.

I sle

ep there on the beach until I can make sea again. After that I sleep always on the rocks, alone.

In the light I am not afraid of the deep, of the darkness close beneath me, but at night the deep frightens me. My dolphin mother understands, my dolphin family understands. As the day stills and the light dims and the sun melts into a pool of spreading red, the sea quiets and we turn toward the nearest cay and I climb from the sea, trailing weeds and long ribbons of grass strung over my shoulders and through my hair. I make a nest for myself with my good hands, pulling wide leaves around me. I make a nest for my lonely sleep and wrap myself in my long, long hair, and give myself to the dark while always within reach, I hear the sound of my family breathing, blowing softly offshore, waiting for morning.

Sometimes it is good to be on land, to be alone. In the sea there is the always touching, the always talking, the always moving. Sometimes I like the quiet. I like the feel of land under my feet. But most times it is dolphin company inside and outside that feels so good.

Sometimes, in the day, sharks will come. They are simple, those sharks. They are simple as rocks. When they come, my family knows what to do. They take turns swimming very fast, and one by one, bang, they smash into the shark, catching it on the side. And after a crash or two or three the shark will swim slowly away, no fights, no bites. But sometimes the shark drops down, down, out of sight, through the gloom where a thousand blind eyes, where a thousand hungry mouths, wait below in the dark for supper to drift past.

But the orca is not simple like the shark. The orca is quick like a stick of lightning. Sometimes the orca can be near and it is safe. I will watch him, beautiful black and white, bold swimmer, big, brave brother, but sometimes the orca will come thinking to eat dolphins, and when he comes thinking that, he always does. And then the ocean has a different feel, and there is fear, and flight and struggle, and in the end sadness, and there is a new song to sing about the dolphin who was and is no more, about the orca who came hungry and ate a brother. And for a while everything is different in the sea. The sound is different, the taste is different. Until the difference becomes part of the long song.

Witness

Witness Safekeeping

Safekeeping Sable

Sable Out of the Dust

Out of the Dust Letters From Rifka

Letters From Rifka The Music of Dolphins

The Music of Dolphins Wish on a Unicorn

Wish on a Unicorn A Light in the Storm

A Light in the Storm